Integrated pest management

Integrated Pest Management, or IPM as it's often called, uses biological, cultural and chemical practices to control pests in agriculture. While it doesn't mean excluding all pesticides, by introducing beneficial insects as a pest prevention tactic, growers can reduce their usage and use chemicals more selectively. 'Our mission is to help growers manage their pests,' entomologist and Bugs for Bugs founder Dan Papacek says.

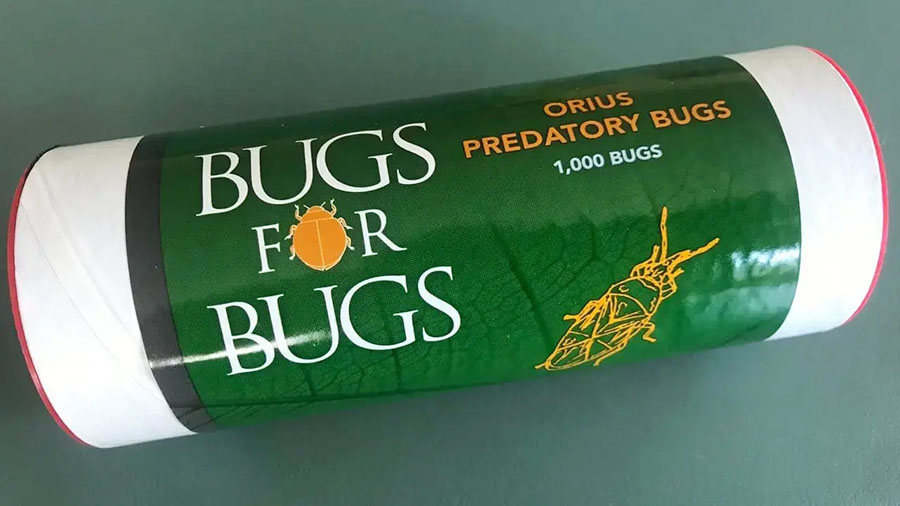

Queensland-based Bugs for Bugs specialises in scientific solutions for pest management. They produce beneficial insects and mites, offering alternatives to conventional pesticides. The company also conducts ongoing research and development into biological control and fruit fly management.

Our mission is to help growers manage their pests.

'While we do produce and supply a range of biological control agents, they're only part of the solution,' Dan says. 'A lot of people assume that they're going to replace chemicals with bugs, and it's not quite like that. However, the beneficial insects we produce can be important tools in that process.'

Encouraging bugs at home

Aphidius Colemani, the natural enemy of many aphid species.

Aphidius Colemani, the natural enemy of many aphid species.

Dan says a few things can make or break the introduction of an integrated pest management system and the development of beneficial bug populations. 'There's a range of things [growers can do], but I can't give you a black-and-white, quick-fix answer for every situation because it varies by crop, soil type, location, climatic conditions and things like that,' Dan says. 'Ultimately, however, I believe we get better results when we have more biodiversity.'

Small switches in management can help, including introducing a diverse range of habitats and food for insects. 'So things like interplanting with flowering plants or crops. Also, things like strip intercropping where you break up the monoculture by having so many rows of a crop and then having so many rows of something else.'

We get better results when we have more biodiversity.

'Things like rotational cropping, things like mulches and better soil management all play a part in getting better environmental conditions.' Dan says for some growers, choosing to grow insect-friendly plants like flowers can be a difficult decision if it takes up space usually reserved for commercial crops. 'I would suggest that in the long term, they'll actually be financially better off. Because if they can reduce their pesticide usage and also improve their sustainability, those things can be hard to quantify but they can improve [crops'] growth.' However, without building those good environments first, Dan says releasing beneficial bugs will not be as effective.

Things like rotational cropping, things like mulches and better soil management all play a part in getting better environmental conditions.

'There's simply no point in releasing biocontrol agents, nor expecting naturally occurring biocontrol agents to help you in your crop if you've got a hostile environment,' he says. 'That hostile environment could be hostile for many reasons. Often it's because of pesticides; it's also often because you've got a depauperate environment - that's just not inviting.'

Creating a healthy environment and introducing beneficial insects before the pests become a significant problem is also important. Dan says biocontrol agents work best as a prevention rather than a cure.

Bugs and their benefits

Native Australian ladybird beetle hunting aphids

Native Australian ladybird beetle hunting aphids

Bugs for Bugs can provide beneficial insects, also called biocontrol agents or beneficials, that can help manage things like aphids, some scale insects, mealy bugs, mites, thrips and caterpillars. For use in nurseries and greenhouses, they have insects that can help with fungus gnats and shore flies. They also supply beneficial insects that target silverleaf whiteflies, a pest prevalent in vegetable crops.

Beyond horticulture, Bugs for Bugs also has control agents that can benefit animal industries, such as parasitic wasps for flies in feedlots, piggeries and chicken farms. To see a full list of products that Bugs for Bugs supplies, check their website here. 'We're also increasingly getting interest from the home gardening market and backyarders,' Dan says.

We're seeking ways to work with pesticides more compatibly. To minimise the use of pesticides should be our goal.

While Dan makes it clear that beneficial insects can't solve every pest problem, he says neither can chemicals, noting how some pests like thrips or spider mites can get worse after each round of spraying. 'It's not so much that we're in competition with pesticides, but we're seeking ways to work with pesticides more compatibly. And to minimise the use of [pesticides] should be our goal,' Dan says.

Introducing beneficials

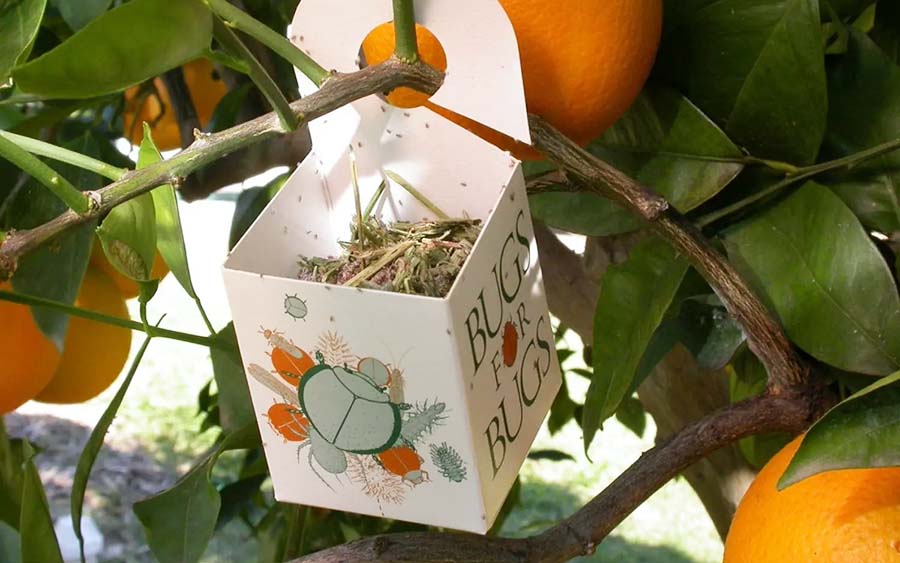

A boxload of lacewing larvae preparing to go to work.

A boxload of lacewing larvae preparing to go to work.

The first step in introducing beneficial insects to a farm is understanding what insects and pests growers already have. 'That's not easy, especially for growers who may misidentify the insects,' Dan says. 'There have been cases where growers want to spray chemicals to control beneficials in their crops because they didn't know the difference.'

Having a pest management consultant or entomologist to advise growers is a great step, but they can be hard to find and hire. 'Having said that, most growers who've been growing for a while do get to know what is most likely going to be a problem for them.'

Bugs for Bugs ships products around Australia, usually by express post or courier. Due to the delicate nature of live insects, it aims to have insects arrive within 24 hours. Some species, such as ladybirds, are transported as adults or as eggs that hatch around the time of arrival. 'Generally, you get more eggs per dollar because they're smaller and less costly to produce,' Dan says.

Placement of the insects depends on the specific crops and pests, but generally, the closer they're released to their food source the better. 'Some of them, we simply release them, like the wasps where you just open the lid of the container and let them fly out,' Dan says.

We provide guidelines for the numbers to release per hectare, and we encourage people to release them uniformly over that area, or even better, if they can identify hotspots, to focus on the hotspots.

However, the team is also experimenting with things like drone releases and developing slow-release sachets that provide for beneficials throughout their life cycle. Each sachet contains food for the predators so they can continue to breed and emerge into the crop over time.

'We provide guidelines for the numbers to release per hectare, and we encourage people to release them uniformly over that area, or even better, if they can identify hotspots, to focus on the hotspots.' One thing Dan says makes beneficial insects different to pesticides is that they lack a well-defined 'dose-response'.

'Unlike chemicals, with beneficial insects and mites, more is better, but they cost money. So we're trying to find the sweet spot where we can release our beneficials and do it for the least cost. And that can be challenging because it varies, depending on the crop and the levels of the pest.'

Dan says that introducing beneficials early, before you see pests at a problem level, makes the insects more cost-effective and able to build their own populations in the field. 'Say you've got a crop that typically has problems with aphids. The minute you see aphids, even at low levels, get your beneficials established then, and let them build up in the crop and work for you at the outset, rather than waiting for them to be a problem.' Dan sees parallels between how we manage pests and how we manage human health, saying the system is geared towards quick fixes.

Excessive chemical use is like constantly using antibiotics to fix an illness in the human body when the underlying problem should be addressed first. Having healthy populations of 'good' bugs to keep the 'bad' bugs in check keeps the body well enough not to need to see the doctor. Likewise, by adopting an integrated pest management system and focusing on building a healthy environment for beneficial insects, farmers are working towards a long-term overall healthy solution.