Calves in the weaning yard.

Calves in the weaning yard.

In 2018, the Gallaghers switched to an early calf-weaning program, with the idea that a cow without its calf would be more energy efficient and better able to maintain condition.

Previously, weaning would happen in March/April. Now, it happens anytime between October and January, depending on the season. This way, the PTIC (Pregnancy Tested in Calf) cows can put all their energy into maintaining condition rather than feeding their calves.

When the Gallaghers initially made the switch to early weaning six years ago, they were hesitant to pull off the smaller calves, so they did a trial run with bigger calves only. Now, they wean whole mobs at once, treating smaller calves differently as needed.

Weaning one mob - 80 cows and 75-80 calves - at a time, the program averages 10 days in duration. The mob is brought into the weaning yard with a feed trough in the middle; calves are herded to one side of the trough and the cows on the other.

To start with, the Gallaghers place good-quality lucerne hay in the trough to coax the calves to eat before starting the calves on a grain ration. The grain ration is a mix of cracked lupins, cracked barley and feed additive.

The amount of grain calves are fed increases very gradually, beginning at 100 g per day, then 100 g morning and night, then 200 g morning and night, right up until they are eating 1 kg per day by the end of the 10-day program.

You have to start with a small amount of grain, and if they don't eat it all, don't increase the ration.

'Once they're on 1 kg a day, their weight gain is 1-1.2 kg per day,' Gerard says. 'And when they are on that amount, they can go onto a self-feeder back out in the paddock, which increases the development of their rumen and makes them a much more efficient animal.'

While the program's approximate duration is 10 days, careful monitoring while increasing the ration is more important than keeping the duration of the program short.

'When we started doing this, we were probably overfeeding the calves and getting a few sick ones,' Gerard says. 'You have to start with a small amount of grain, and if they don't eat it all, don't increase the ration, and even back it off if you have to. If the calves are stuck on 300 g daily and not finishing it all, stay on 300 g. Don't go up until they all start eating again.

'The big thing is you have to be flexible with the program. You have to get animal health right for a start, then feed in increments and monitor what's going on.'

The big thing is you have to be flexible with the program. You have to get animal health right for a start, then feed in increments and monitor what's going on.

The Gallaghers feed out the grain using a bucket, and while the process is labour-intensive, it means opportunities to monitor the mob are plentiful.

Gerard and Lucy pay particular attention to any shy feeders and pull any animals out of the main mob that aren't eating well. Separating them into weight ranges can also address the shy feeder problem, as having more similarly sized animals leads to fewer pecking order problems and, subsequently, fewer shy feeders.

After the calves have been successfully weaned, they are moved onto high-performance pastures or oat crops, where they remain for the next 15-18 months before being sold. During this time, weight gain is 1-1.3 kg per day.

The top-end steers are then sent to NH Foods's Whyalla feedlot north-west of Texas, Queensland, or the company's Bective feedlot, just out of Tamworth. Any steers not sent to NH Foods are fed through to Woolworths, with the aim of hitting a liveweight of 550 kg before sending. Any heifers not kept on for joining (120 heifers are joined each year) are also fed through to Woolworths.

While the calves are placed on to good-quality paddocks following weaning, the cows are moved onto grass country or grazing country. However, without having to feed the calves, the lower-quality country is sufficient to ensure the cows do not drop in condition.

'The cows have the benefit of not having a calf on them drawing energy,' Gerard says. 'So we can put the cows onto country with a stocking rate of 10 DSE/ha, rather than a DSE of 16, which is what they would have needed to be on if they still had the calves on them.'

In terms of exactly when to wean the calves, Gerard says if the season is looking tight, weaning early is the best choice, so cows and calves can be fed separately and as efficiently as possible.

'If a cow has a calf lactating on it, it becomes a bit inefficient. Once you get a 250 kg weaner sucking on a cow, it does take a fair bit of energy from the cow to produce that milk, but the calf at that age doesn't need milk to survive,' he says.

Last year's drop were weaned in October when they were just 80 kg, with the extreme earliness due to a need to get the cows cycling again.

'[In 2023] we hit the wall in a bad season, and we thought the cows were going to struggle to cycle with calves on them,' Gerard says. 'So we weaned early, and the cows got in-calf very well, cycling just a few weeks after we took the calves off.'

If weaning early, producers need to be prepared to feed calves if the season remains dry, which is what has happened to the Gallaghers in 2024.

'We had a good rain in November last year, then a terribly dry first three months of 2024, so those calves have had to have supplementary feed. They will go onto an oat crop fairly soon,' Gerard says.

And while the supplementary feeding is a downside, early weaning allowed the Gallaghers to retain their breeding stock, thanks to lowered energy requirements.

'We were able to keep our numbers, rather than selling a lot of cattle on a depressed market, which was last year. It's protected our income for the end of this year because we have kept the stock,' Gerard says.

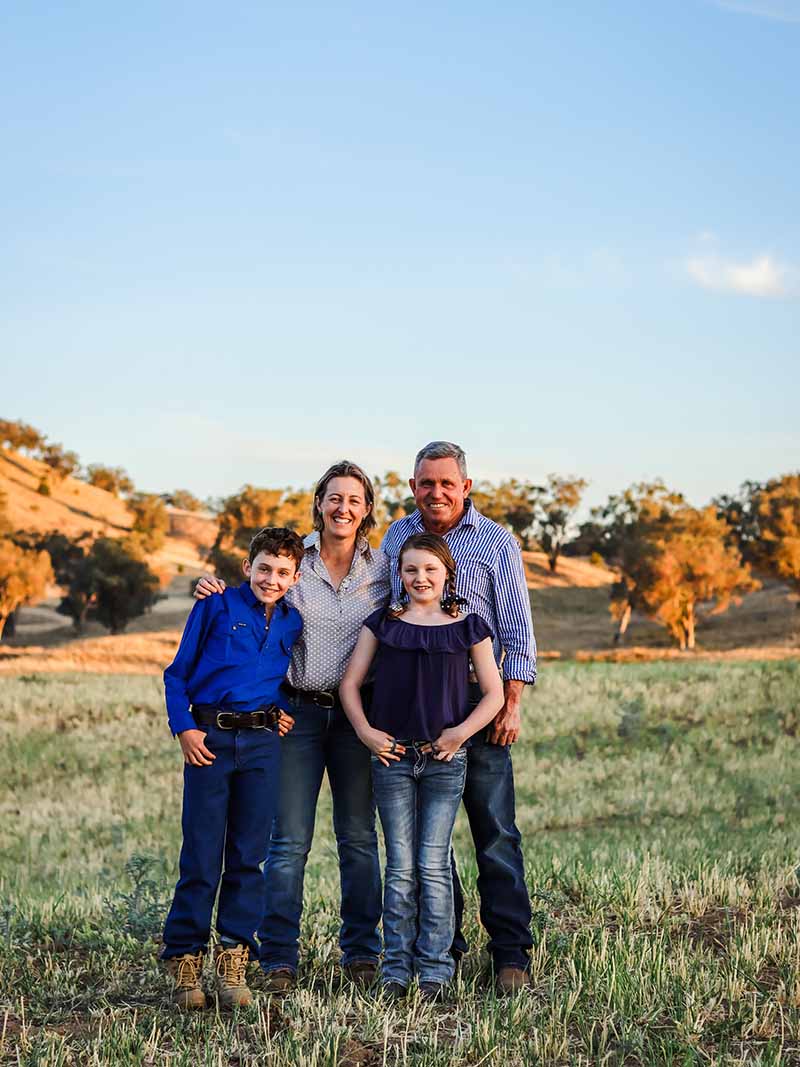

The Gallagher family, Tarrabah Pastoral Co.

The Gallagher family, Tarrabah Pastoral Co.