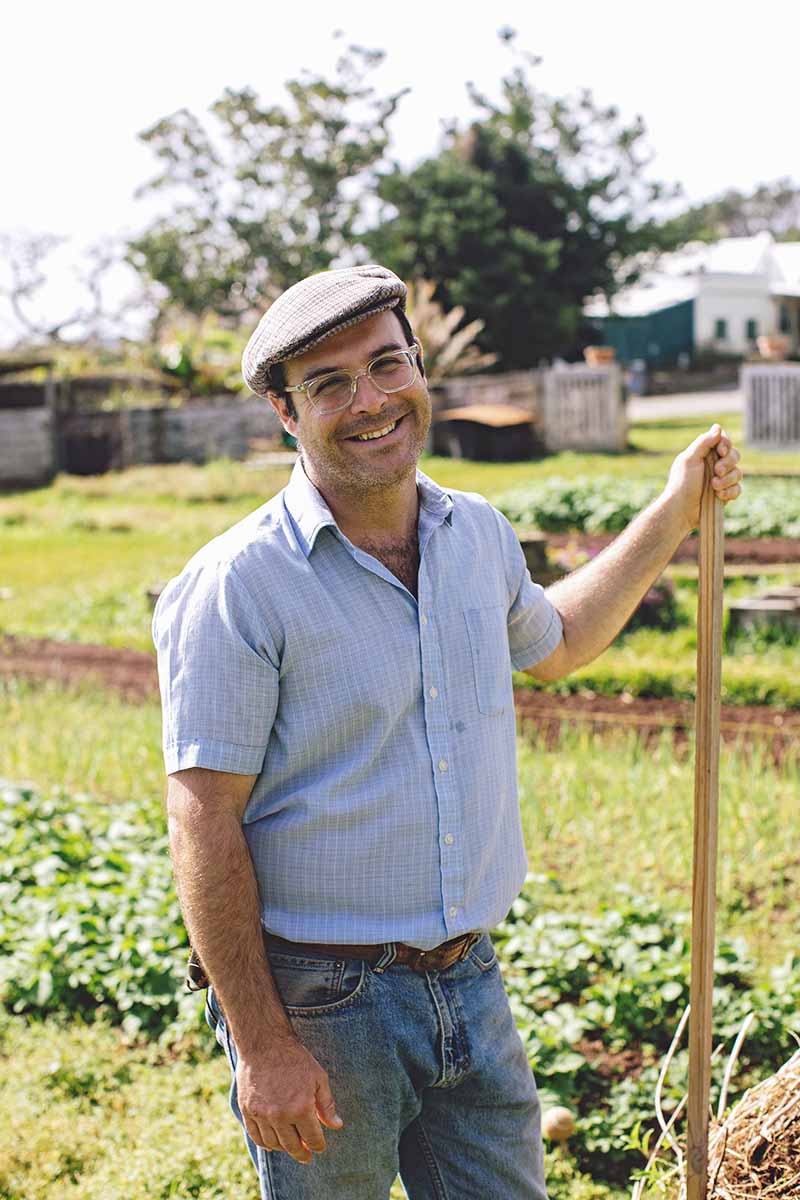

When COVID-19 spread throughout the world, cracks started to show in many countries' supply chains. In the tiny territory of Bermuda, where nearly all food is imported, sustainable farming educator Chris Faria said it was a huge wake-up call.

'There was such a disruption to the food supply chain that there were definitely areas of shelves that were empty,' Mr Faria said. 'A lot of products just weren't there.'

Food security is defined by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) as: 'When all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.'

To find out more about the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Bermuda's food security, a 2024 report was published in the National Library of Medicine.

The shake-up to supply chains highlighted the systemic challenges in Bermuda's food systems: limited farmlands, a tiny population of farmers, and a heavy reliance on imports.

Bermuda's agriculture is relegated to tiny plots of land, often just half an acre, tucked away between suburbs, on the sides of roads and squeezed between golf courses and parks. There are only 18 registered farmers in a population of around 65,000 people, growing vegetables and fruits, selling to some shops, as well as at roadside stalls.

'The reality is that less than half the agricultural reserve [land that's protected for farming in Bermuda] is being farmed right now,' Mr Faria said.

Prices of food in Bermuda are astronomical and continue to rise. In March 2024, 1 litre of milk cost A$6.72, and a loaf of white bread cost A$12.46.

Beyond the economic drivers of limited local food supply, Chris says societal and historical factors also need to be taken into consideration as to why agriculture hasn't been seen as a viable industry to enter.

Bermuda was first settled in 1609 by the British and was never home to an indigenous people. Under early colonial rule, landowners brought slaves from Africa, the Caribbean and North America to grow maize, tobacco, arrowroot and other crops.

With the history of slavery comes a generational trauma - a reason why some People of Colour aren't interested in working in agriculture today.

'We have a majority Black Bermudian population, and many of their ancestors were enslaved people, and we've not been able to heal from that trauma yet.'

Chris says the introduction of Portuguese farm labourers like his ancestors in the 1860s drove a further wedge into the social fabric. Newly emancipated Black Bermudians were further disenfranchised from taking up positions in agriculture.

'That's still the Bermuda we live in in 2024, there's lots of guest workers that are brought into Bermuda, and Bermudians don't have access to [some] jobs, and some of those jobs aren't even that appealing for them to take,' he said.

The work of healing that trauma is something Chris doesn't have all the answers for, but he hopes one day more Bermudians will be reconnected with the land and with agriculture.

For Chris, the wake-up call that was COVID-19 inspired him to build an enterprise that combined his love of connecting people with all things growing while helping reduce food insecurity along the way.